Rangefinder sensors have become integral components in a wide array of modern technological applications, fundamentally changing how devices perceive and interact with distance. These sophisticated electronic components measure the distance between the sensor and a target object with remarkable precision, utilizing various physical principles to achieve accurate readings. The core functionality revolves around emitting a signal, whether it be a beam of light, a sound wave, or a radio wave, and then precisely calculating the time it takes for the reflection to return. This time-of-flight measurement is then converted into a precise distance value, enabling machines to understand their spatial environment.

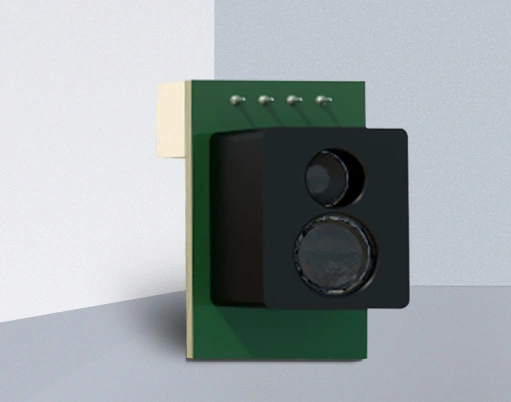

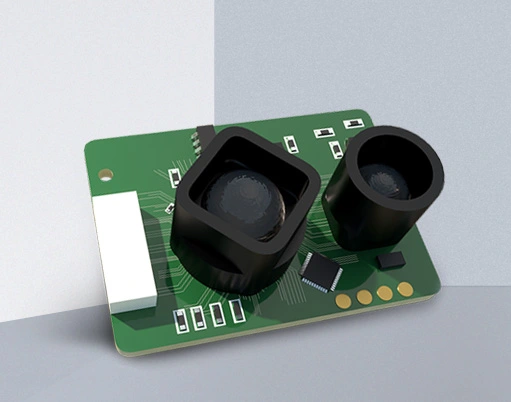

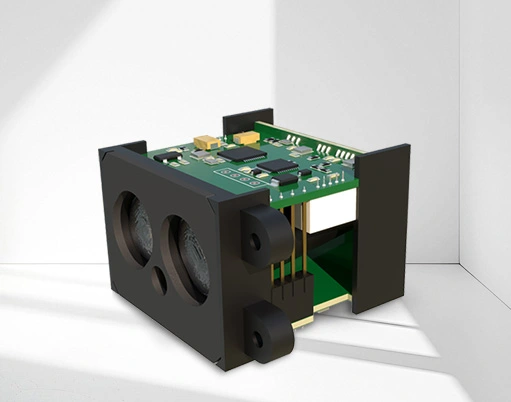

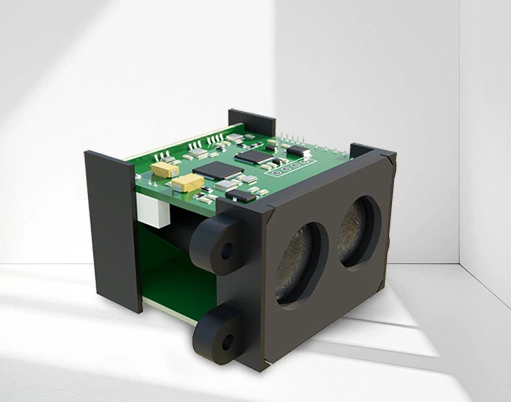

The evolution of rangefinder technology has been significant. Early systems were often bulky, expensive, and limited in accuracy. Today, advancements in microelectronics and signal processing have led to the development of compact, affordable, and highly reliable sensors. Two primary methodologies dominate the market: laser-based and ultrasonic rangefinders. Laser rangefinders, or LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) in more advanced forms, use focused light beams. They offer exceptional accuracy over long distances and are prevalent in surveying equipment, advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) in vehicles, and even in smartphones for camera autofocus and augmented reality features. The laser diode emits a pulse, and a high-speed clock measures the nanosecond-level return time.

Ultrasonic rangefinders, on the other hand, operate using sound waves at frequencies above the human hearing range. They are highly effective for shorter distances and are less affected by ambient light conditions, making them ideal for applications like parking sensors in automobiles, liquid level sensing in tanks, and simple robotics for obstacle avoidance. These sensors emit a chirp of ultrasonic sound and listen for the echo. Their operation can be influenced by factors like temperature and air turbulence, but they remain a cost-effective solution for many proximity-sensing needs.

Beyond these, other technologies like infrared (IR) and radar-based rangefinders find niche applications. IR sensors are common in simple distance measurement modules for hobbyist projects and some consumer electronics, while radar sensors, which use radio waves, are crucial in automotive adaptive cruise control and long-range detection due to their ability to perform well in adverse weather conditions.

The practical applications of rangefinder sensors are vast and continually expanding. In the automotive industry, they form the backbone of safety features. Multiple sensors around a vehicle's perimeter create a proximity map, enabling automatic emergency braking, blind-spot monitoring, and self-parking capabilities. This network of sensors is a foundational element in the development of autonomous vehicles, allowing them to navigate complex environments safely.

In consumer electronics, the integration of miniature laser rangefinders has revolutionized smartphone photography. By instantly and accurately measuring the distance to a subject, these sensors enable cameras to achieve faster and more precise autofocus, leading to sharper images, especially in portrait mode where background blur (bokeh) is artificially enhanced. Furthermore, they are key enablers for augmented reality apps, allowing digital objects to be placed realistically within a physical space by understanding depth.

Industrial and robotics applications heavily rely on these sensors for automation and precision. Robotic arms use rangefinders for precise positioning and pick-and-place operations. Drones utilize them for terrain following, obstacle detection, and safe landing. In construction and surveying, high-precision laser rangefinders are indispensable tools for measuring distances, areas, and volumes with minimal human error, improving efficiency and accuracy on job sites.

Even in smart home devices, rangefinder sensors contribute to functionality. Robot vacuum cleaners map rooms and avoid furniture using a combination of sensors. Smart televisions or displays might use simple proximity sensors to detect when a user is present to turn on or adjust settings. The technology's versatility is its greatest strength.

Looking forward, the trajectory for rangefinder sensor technology points toward even greater miniaturization, reduced power consumption, and enhanced integration. The development of solid-state LiDAR, which has no moving parts, promises to make high-resolution 3D mapping more affordable and robust for mass-market applications. Furthermore, sensor fusion—combining data from rangefinders with cameras, inertial measurement units, and other sensors—will lead to more context-aware and intelligent systems. As the demand for machines that can see, understand, and navigate the physical world autonomously grows, the humble rangefinder sensor will undoubtedly remain a critical piece of the technological puzzle, quietly and precisely measuring the space between innovation and reality.