In today's interconnected and automated world, electrical sensors serve as the fundamental building blocks for gathering critical data from the physical environment. These sophisticated devices act as the sensory organs of modern electronic systems, converting various forms of physical stimuli—such as light, pressure, temperature, motion, or magnetic fields—into precise, measurable electrical signals. This conversion process enables machines, control systems, and computers to perceive, analyze, and respond to their surroundings with remarkable accuracy and speed. The core principle behind most electrical sensors involves a change in an electrical property—like voltage, current, capacitance, or resistance—in response to a specific external input. This signal is then conditioned, processed, and interpreted by other electronic components to trigger actions, display readings, or feed into complex algorithms for decision-making.

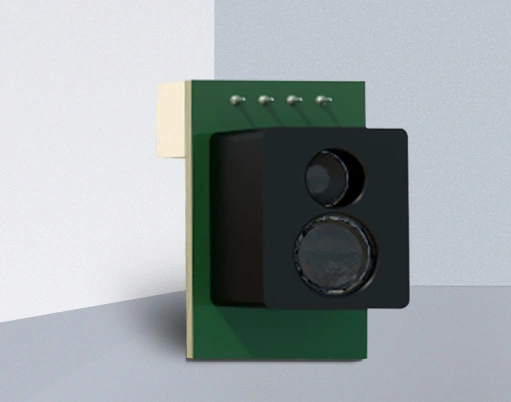

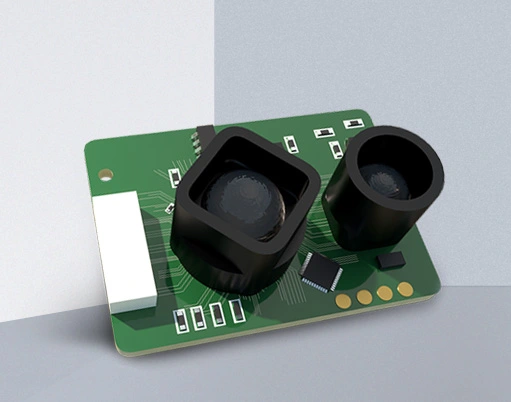

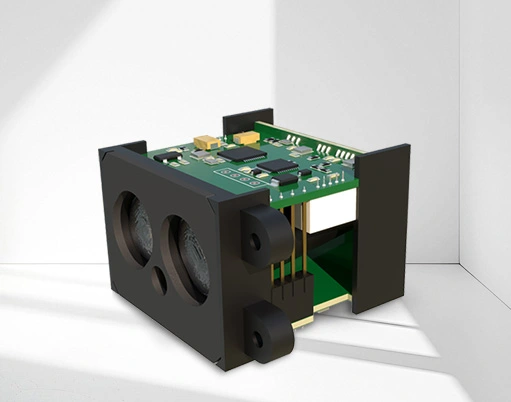

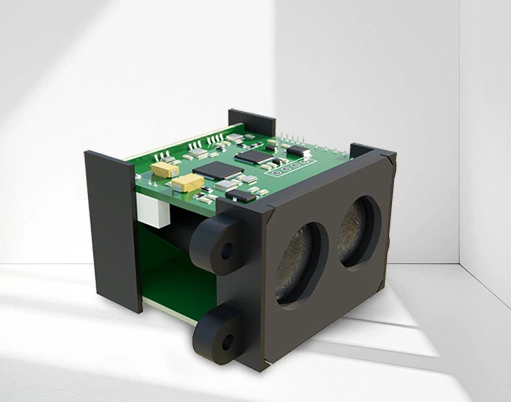

The diversity of electrical sensors is vast, each engineered for a specific type of measurement. Proximity sensors, for instance, detect the presence or absence of nearby objects without physical contact, commonly using inductive, capacitive, or ultrasonic technologies. They are indispensable in manufacturing assembly lines for object counting and position verification. Temperature sensors, like thermocouples and resistance temperature detectors (RTDs), provide crucial data for climate control systems, industrial process monitoring, and medical devices. Pressure transducers convert fluid or gas pressure into an electrical output, vital for automotive engine management, aviation, and hydraulic systems. Meanwhile, optical sensors, including photodiodes and infrared sensors, are key to applications ranging from ambient light detection in smartphones to precise alignment in robotics.

The applications of electrical sensors permeate every sector of industry and daily life. In the automotive industry, a network of sensors monitors everything from engine temperature and oxygen levels in exhaust to wheel speed for anti-lock braking systems (ABS) and tire pressure. The rise of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and Industry 4.0 has further amplified their role, with sensors embedded in machinery providing real-time data on performance, predicting maintenance needs, and optimizing production efficiency. In smart homes, sensors adjust lighting based on occupancy, regulate thermostats for comfort and energy savings, and detect smoke or water leaks for safety. The healthcare sector relies on biosensors for patient monitoring and diagnostic equipment, while environmental science uses specialized sensors to track air and water quality.

Selecting the appropriate electrical sensor for an application requires careful consideration of several parameters. Key specifications include sensitivity (the minimum input required to produce a detectable output), range (the minimum and maximum values it can measure), accuracy (closeness to the true value), resolution (the smallest change it can detect), and response time. Environmental factors such as operating temperature, humidity, and potential exposure to chemicals or vibrations also dictate the choice of sensor housing and materials. Furthermore, the output signal type—analog (e.g., 4-20 mA, 0-10V) or digital (e.g., I2C, SPI)—must be compatible with the data acquisition system or controller it interfaces with.

Looking ahead, the future of electrical sensor technology is driven by trends toward miniaturization, enhanced intelligence, and wireless connectivity. The development of Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) has led to incredibly small, low-power, and cost-effective sensors now found in every smartphone and wearable device. The integration of artificial intelligence and edge computing is giving rise to "smart sensors" that can perform initial data processing and analysis locally, reducing latency and bandwidth needs. Energy-harvesting techniques, which allow sensors to power themselves from ambient light, heat, or vibration, are enabling truly wireless and maintenance-free sensor networks for large-scale infrastructure and remote monitoring. As these technologies converge, electrical sensors will become even more pervasive, accurate, and autonomous, forming the backbone of smarter cities, advanced robotics, and more responsive industrial ecosystems, ultimately creating a more seamlessly measured and managed world.