In today's rapidly evolving technological landscape, inertial measurement units (IMUs) have become fundamental components across numerous industries. These sophisticated sensors, often no larger than a postage stamp, are responsible for tracking motion, orientation, and velocity in a wide array of devices, from consumer electronics to advanced aerospace systems. At its core, an IMU sensor is a combination of several individual sensors packaged together, typically including accelerometers, gyroscopes, and sometimes magnetometers. Each of these components plays a critical role in providing comprehensive motion data.

An accelerometer within the IMU measures linear acceleration—the rate of change of velocity along a straight line. This allows devices to sense movement in three-dimensional space, detecting whether they are moving forward, backward, sideways, up, or down. By integrating acceleration data over time, the sensor can also estimate velocity and position, though this method can accumulate errors. Meanwhile, the gyroscope measures angular velocity, or the rate of rotation around an axis. This is crucial for determining orientation—how an object is tilted or rotated in space. For instance, when you turn a smartphone from portrait to landscape mode, it is the gyroscope data that triggers the screen to reorient itself. Some advanced IMUs also incorporate a magnetometer, which acts like a digital compass by sensing the Earth's magnetic field to determine heading relative to magnetic north. This helps correct for drift errors that can accumulate in the gyroscope over time.

The real power of an IMU sensor lies in sensor fusion, a process where data from these individual sensors is combined using complex algorithms, often running on a dedicated processor or microcontroller. Algorithms like the Kalman filter are commonly employed to merge the noisy, short-term accuracy of the accelerometer with the stable, long-term orientation data from the gyroscope, creating a much more accurate and reliable estimate of the device's true position and orientation. This fusion is essential because each sensor type has its weaknesses; accelerometers are sensitive to vibrations and gravity, while gyroscopes can drift over time. By intelligently combining their outputs, the system compensates for these individual flaws.

The applications of IMU sensors are vast and continually expanding. In the consumer electronics sector, they are ubiquitous in smartphones, tablets, and gaming controllers, enabling features like screen rotation, motion-controlled gaming, step counting in fitness apps, and image stabilization in cameras. The automotive industry relies heavily on IMUs for advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), electronic stability control, and navigation systems, especially in scenarios where GPS signals are lost, such as in tunnels. In robotics, IMUs are indispensable for balance, navigation, and precise movement control, allowing robots to understand their own motion in an environment. Perhaps most critically, IMUs are a cornerstone of aviation and aerospace navigation, providing vital attitude and heading reference data for aircraft, drones, and spacecraft where GPS is unavailable or unreliable.

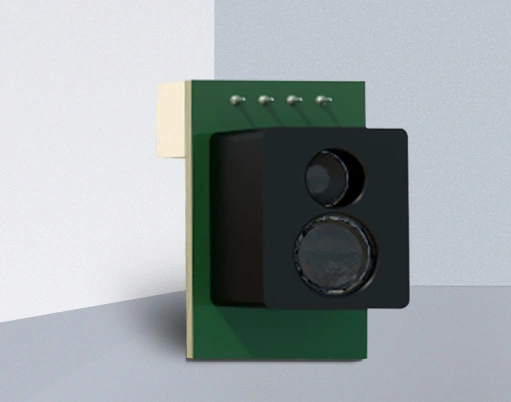

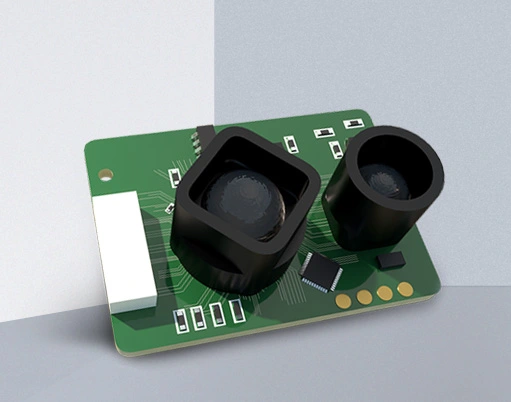

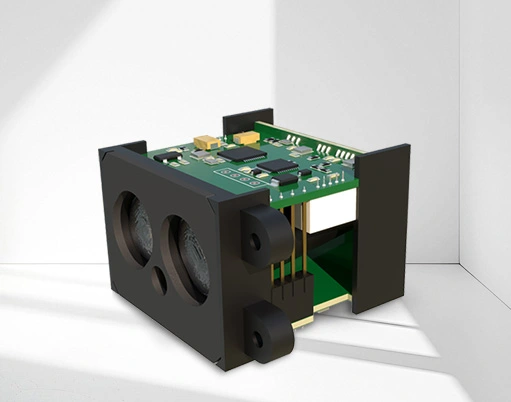

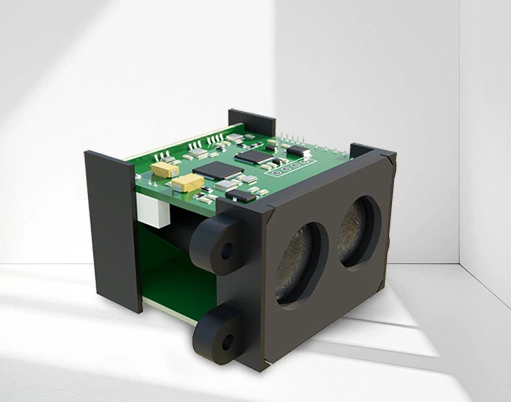

The development of Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) technology has been a key driver in the proliferation of IMU sensors. MEMS fabrication allows these complex electromechanical systems to be manufactured on silicon chips at a microscopic scale, making them incredibly small, lightweight, power-efficient, and cost-effective. This miniaturization has unlocked their use in portable and wearable devices, from smartwatches and VR headsets to medical devices that monitor a patient's posture or movement during rehabilitation.

However, working with IMU data presents significant engineering challenges. All sensors produce inherent noise and bias, and their readings can be affected by temperature changes and electromagnetic interference. The process of calculating position by integrating acceleration data twice is particularly prone to error accumulation, known as drift, where even tiny inaccuracies compound rapidly. This is why IMUs are often used in conjunction with other systems like GPS, cameras, or lidar in a technique called sensor fusion for higher-level navigation systems. Engineers must carefully calibrate the sensors and implement robust software algorithms to filter noise and correct for these errors to achieve usable results.

Looking forward, the future of IMU sensor technology points toward even higher levels of integration, accuracy, and affordability. The next generation of IMUs aims for improved performance in challenging environments, lower power consumption for IoT devices, and tighter integration with other sensing modalities like radar and ultrasound. As autonomous vehicles, augmented reality, and sophisticated industrial automation become more prevalent, the demand for reliable, precise, and compact inertial measurement will only grow, ensuring that the humble IMU sensor remains a critical enabler of innovation across the technological spectrum.