In the modern industrial and technological landscape, the ability to accurately detect and monitor the presence, level, or composition of liquids is paramount. This capability is enabled by a critical device: the liquid sensor. A liquid sensor is a transducer that converts a physical property or condition of a liquid into a measurable signal, typically electrical. Its applications span from ensuring safety in chemical plants to optimizing processes in food and beverage production, and from managing resources in agriculture to enabling precision in medical diagnostics. The core function of these sensors is to provide reliable data for control systems, triggering alarms, initiating actions, or simply logging information for analysis.

The working principles of liquid sensors are as diverse as their applications. One of the most common types is the capacitive liquid sensor. It operates by detecting changes in capacitance between two electrodes. When a liquid, which has a different dielectric constant than air, enters the sensing area, it alters the capacitance. This change is measured and interpreted as a detection event. These sensors are excellent for non-contact level sensing and can detect various liquids through non-metallic container walls. Another widespread technology is the conductive or resistive sensor. It relies on the electrical conductivity of the liquid itself. Two or more probes are inserted into the tank or pipe. When the liquid rises to touch the probes, it completes an electrical circuit, allowing current to flow. The simplicity of this principle makes it robust and cost-effective for point-level detection of conductive fluids like water. However, it is unsuitable for non-conductive liquids such as oils or fuels.

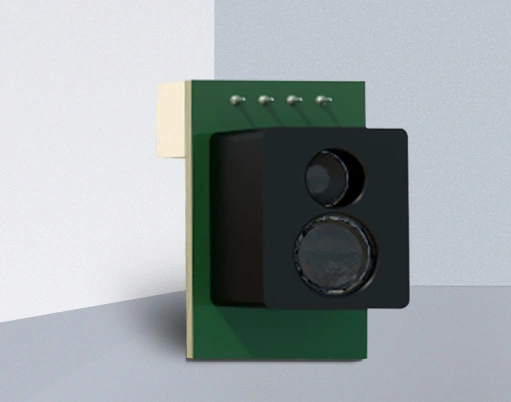

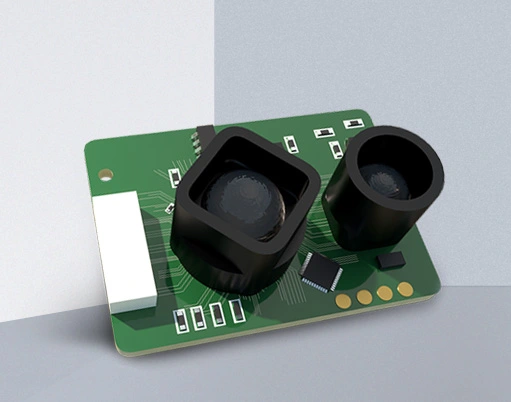

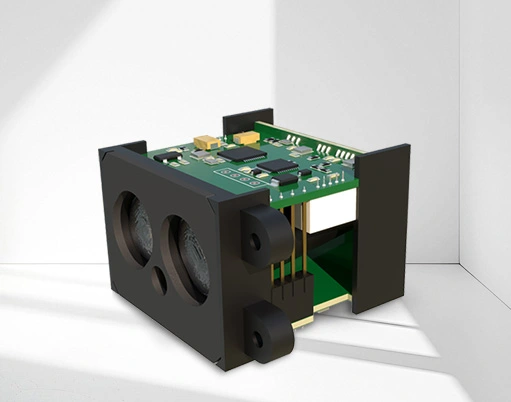

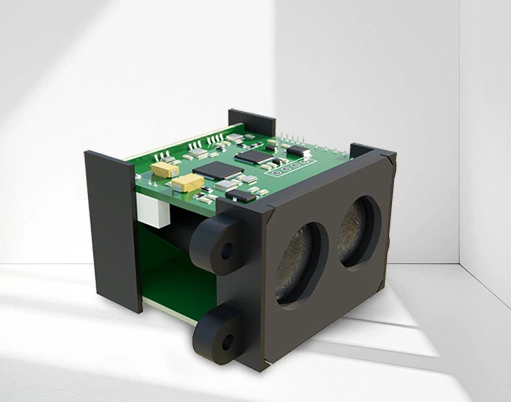

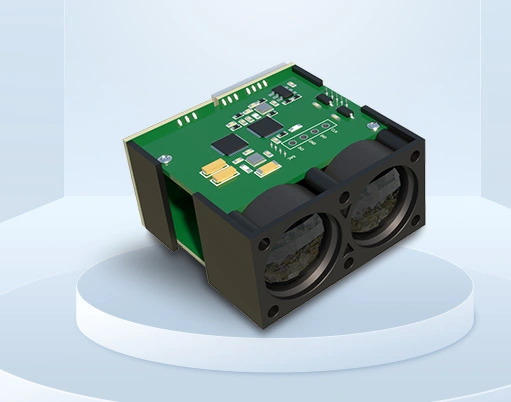

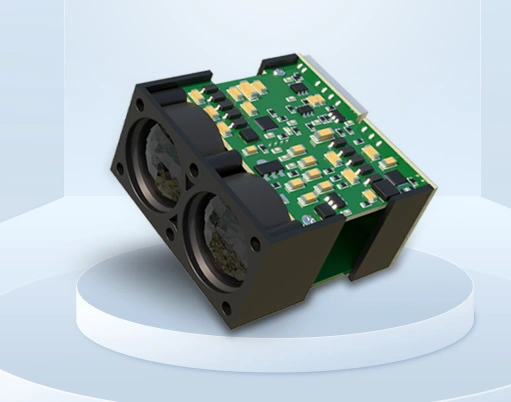

For environments requiring high precision and versatility, ultrasonic liquid sensors are often employed. These devices emit high-frequency sound waves and measure the time it takes for the echo to return from the liquid surface. By calculating this time-of-flight, the sensor can determine the distance to the liquid, thereby measuring its level accurately. They are ideal for harsh conditions involving corrosive liquids, high temperatures, or high pressures, as the sensor does not need to contact the liquid directly. Optical liquid sensors represent another non-contact method. They use infrared or visible light and a photodetector. The presence of liquid alters the light's path through refraction, reflection, or absorption, which is detected by the sensor. These are frequently used in leak detection systems, automotive applications, and consumer electronics for spill detection.

The selection of an appropriate liquid sensor depends heavily on the specific application requirements. Key factors include the chemical properties of the liquid (corrosiveness, conductivity, viscosity), the required measurement (point-level or continuous level, presence/absence), environmental conditions (temperature, pressure, humidity), and necessary certifications for hazardous areas. In the water treatment industry, sensors monitor tank levels and control pump operations to prevent overflow or dry running. In the automotive sector, they check brake fluid levels, coolant levels, and battery electrolyte conditions. The food and beverage industry relies on them for hygiene and process control, often requiring sensors made from food-grade materials like stainless steel 316L. In pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, sensors ensure precise liquid handling in reactors and bioreactors, where sterility and accuracy are non-negotiable.

Emerging trends are pushing the boundaries of liquid sensor technology. The integration of the Internet of Things (IoT) is a significant driver. Modern liquid sensors are increasingly equipped with digital outputs, wireless connectivity, and smart features. This allows for remote monitoring of liquid assets across vast facilities, predictive maintenance by analyzing sensor data trends, and integration into larger automated control systems. Another advancing frontier is the development of multi-parameter sensors. Instead of just detecting presence or level, these sophisticated devices can simultaneously analyze parameters like pH, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, or specific chemical concentrations within the liquid. This provides a much more comprehensive picture of the process or environmental condition. Furthermore, research into novel materials, such as graphene-based sensors, promises even greater sensitivity, miniaturization, and the ability to detect trace contaminants.

Despite their sophistication, the deployment of liquid sensors is not without challenges. Sensor fouling, where deposits build up on the sensing element, can lead to drift or complete failure, especially in dirty or viscous liquids. Regular calibration and maintenance are essential for long-term accuracy. For conductive sensors, electrolysis can corrode the probes over time when used with certain liquids. Environmental factors like extreme temperatures, foam, vapor, or turbulence can also interfere with readings, particularly for ultrasonic and optical types. Therefore, proper installation, housing selection, and a clear understanding of the operating environment are as crucial as selecting the right sensing technology.

In conclusion, the liquid sensor is a foundational component in countless systems that manage our world's liquids. From safeguarding industrial processes to ensuring the quality of our water and the efficacy of our medicines, these devices provide the essential data needed for control, safety, and efficiency. As technology evolves towards greater connectivity, intelligence, and multi-functionality, liquid sensors will continue to become more integral, reliable, and insightful, forming the sensory backbone of smarter and more responsive liquid management systems across all sectors.