In today's interconnected world, sensors serve as the fundamental building blocks of countless systems, from smartphones and smart homes to industrial automation and autonomous vehicles. However, the concept of "sensor limited" has emerged as a critical challenge, describing scenarios where the capabilities, accuracy, or reliability of sensors become the primary bottleneck for system performance. This limitation is not merely a technical hiccup; it represents a significant barrier to innovation, safety, and efficiency across various sectors.

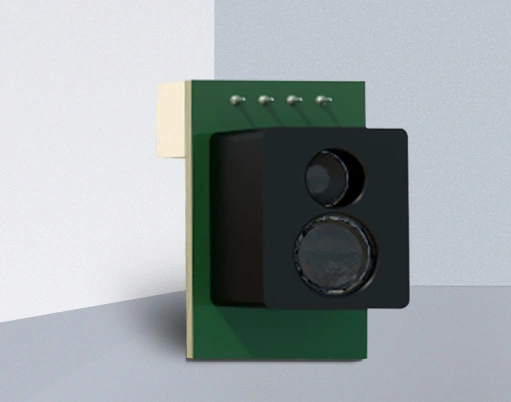

At its core, being sensor limited means that the overall functionality of a device or system is constrained by the physical and operational boundaries of its sensory components. These boundaries can manifest in several ways. One of the most common is range limitation, where a sensor cannot detect objects or signals beyond a specific distance. For instance, a LiDAR sensor on a self-driving car has a finite effective range, beyond which it cannot perceive obstacles, potentially creating dangerous blind spots. Similarly, environmental factors like extreme temperatures, humidity, dust, or electromagnetic interference can severely degrade sensor performance, leading to inaccurate data or complete failure. This is a paramount concern for sensors deployed in harsh industrial settings or outdoor applications.

Another critical aspect is resolution and accuracy. A sensor limited by low resolution cannot distinguish between fine details, which is crucial in applications like medical imaging or precision manufacturing. Accuracy limitations mean the sensor's readings consistently deviate from the true value, which can have cascading effects on decision-making algorithms. For example, an inaccurate temperature sensor in a climate control system can lead to excessive energy consumption or uncomfortable conditions. Furthermore, latency—the delay between a physical event and the sensor's electronic output—can be a limiting factor in time-sensitive applications like high-frequency trading or real-time robotic control.

The impact of these limitations is profound. In the realm of the Internet of Things (IoT), sensor limitations can compromise the entire network's data integrity, leading to faulty automation and wasted resources. In healthcare, limitations in biosensors can affect the reliability of remote patient monitoring, with serious implications for diagnosis and treatment. For consumer electronics, limitations in image sensors directly affect photo and video quality, influencing user satisfaction and market competition.

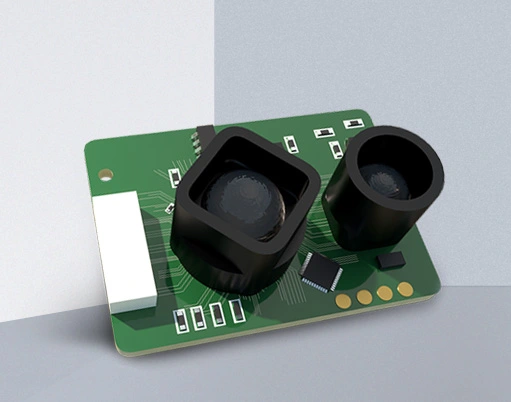

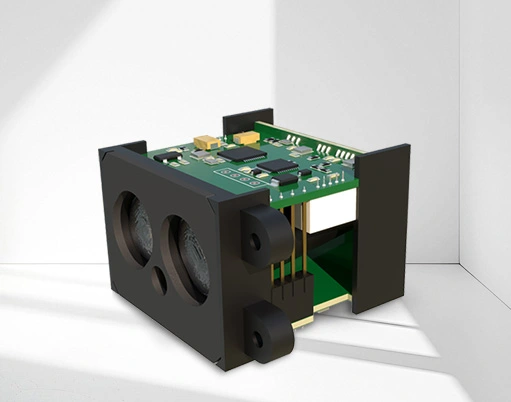

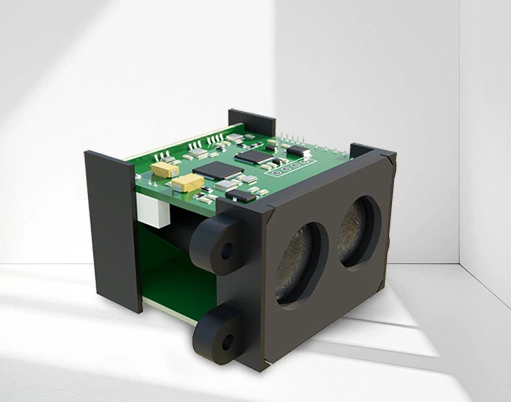

Addressing the challenge of being sensor limited requires a multi-faceted approach. Technological innovation is at the forefront. Researchers are continually developing new sensor materials, such as graphene-based sensors, which offer higher sensitivity, flexibility, and durability. Advancements in micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) allow for the creation of smaller, more power-efficient, and more robust sensors. Improving signal processing algorithms is equally vital. Sophisticated software can filter out noise, correct for known biases, and fuse data from multiple sensor types (a process called sensor fusion) to create a more accurate and reliable composite reading than any single sensor could provide alone.

System design also plays a crucial role. Engineers can implement redundancy by using multiple sensors of the same type to cross-verify data or different types of sensors to cover each other's weaknesses. For instance, a vehicle might combine radar, camera, and ultrasonic sensors to overcome the individual limitations of each. Regular calibration and maintenance protocols are essential to ensure sensors continue to operate within their specified parameters over time.

Moreover, a paradigm shift is occurring from merely collecting more data to collecting smarter data. This involves contextual awareness, where sensors are designed or programmed to understand their operating environment and adjust their behavior accordingly. Edge computing, where data is processed locally on the device rather than being sent to a distant cloud server, can reduce latency and alleviate bandwidth constraints caused by high-frequency sensor data streams.

Ultimately, understanding and mitigating sensor limitations is not about seeking perfection but about managing constraints intelligently. By acknowledging that sensors are inherently limited, developers and engineers can build more resilient, adaptive, and effective systems. The future of technological progress hinges on our ability to push these sensory boundaries through material science, intelligent algorithms, and innovative system architectures, transforming the challenge of being sensor limited into an opportunity for groundbreaking advancement.