Distance sensors are fundamental components in modern automation, robotics, and IoT systems. Their primary function is to detect the presence of an object and measure the gap between the sensor itself and the target. The performance of any distance-sensing application hinges critically on one key specification: the sensor's range. This parameter defines the minimum and maximum distances over which the sensor can operate reliably and accurately. Understanding the nuances of sensor range is not merely about knowing the numbers on a datasheet; it involves grasping the factors that influence it and how it interacts with real-world conditions.

The concept of range is typically expressed as two values: the minimum sensing distance and the maximum sensing distance. The minimum distance is the closest point at which the sensor can still provide a stable reading. Objects placed closer than this point may not be detected, or the signal may become saturated, leading to errors. The maximum distance represents the farthest point at which the sensor can reliably detect an object and return a valid measurement. Beyond this point, the signal strength diminishes to a level where it cannot be distinguished from background noise or environmental interference. The span between these two points is the effective operating range.

Several core technologies underpin distance sensing, each with distinct range characteristics and limitations. Ultrasonic sensors emit sound waves and calculate distance based on the time-of-flight of the reflected echo. They are known for their relatively long range, often capable of measuring several meters, and are immune to the color or transparency of the target. However, their accuracy can be affected by temperature, humidity, and the texture of the object's surface. In contrast, infrared (IR) proximity sensors, which often use triangulation or intensity-based methods, generally offer shorter ranges, typically up to a few tens of centimeters. Their performance is highly susceptible to ambient light and the reflectivity of the target material; a shiny white object will return a much stronger signal than a matte black one at the same distance.

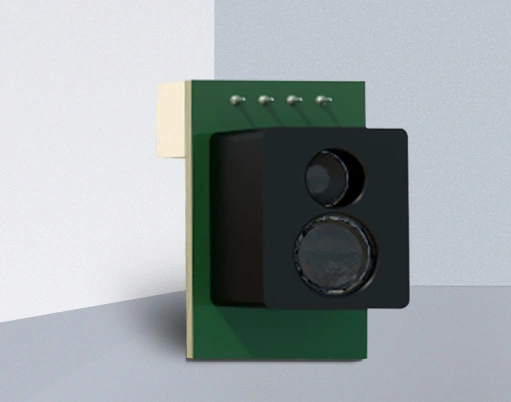

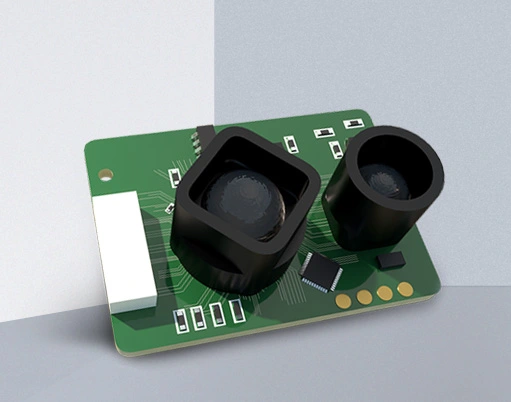

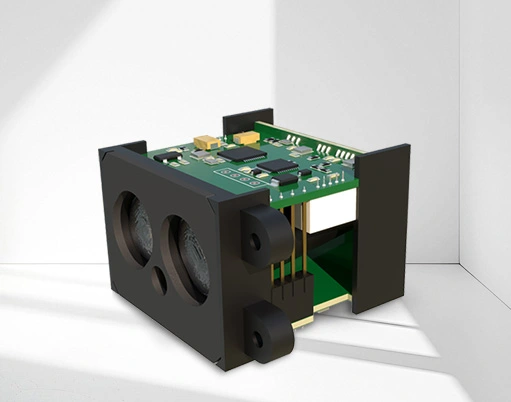

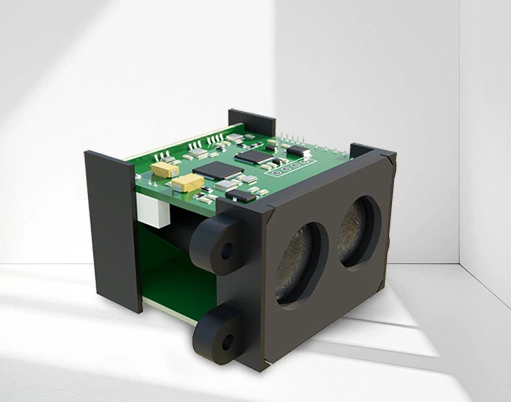

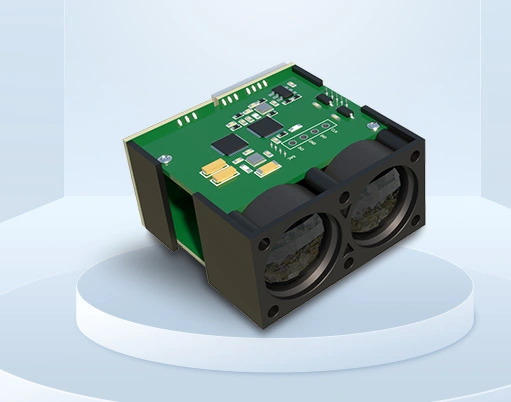

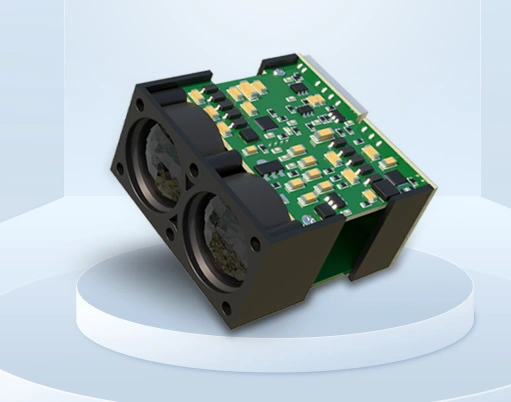

Laser-based sensors, such as LiDAR or laser time-of-flight (ToF) sensors, represent the high-precision end of the spectrum. They can achieve very long ranges—from several meters to hundreds of meters—with exceptional accuracy. Their narrow, focused beam allows for precise targeting, but they come at a higher cost and can be sensitive to environmental conditions like fog or dust. Inductive and capacitive sensors are used for very short-range, non-contact detection of metallic or any material objects, respectively, with ranges usually limited to millimeters.

The stated range on a product specification is determined under ideal, controlled laboratory conditions. In practical deployment, the effective range can be significantly reduced. Environmental factors are primary contributors to this reduction. For optical sensors (IR, laser), ambient light from the sun or other sources can flood the receiver, drastically cutting the maximum range. Dust, smoke, or fog can scatter or absorb the emitted signal. For ultrasonic sensors, air turbulence, temperature gradients, and high background noise can interfere with the sound wave propagation. The target object's properties are equally critical. Its size, shape, angle (orientation), and surface characteristics (color, reflectivity, texture) directly impact how much signal is reflected back to the sensor. A small, dark, or absorbent target at the far end of the specified range may simply not return a detectable signal.

Selecting a sensor with an appropriate range is a balancing act. Choosing a sensor with a maximum range far exceeding the application's needs can seem like a safe bet, but it may lead to unnecessary cost, power consumption, and potential interference from distant, unintended objects. Conversely, selecting a sensor whose maximum range is too close to the required measurement distance leaves no margin for error. A good practice is to select a sensor whose nominal maximum range is 1.5 to 2 times the actual maximum distance needed in the application. This provides a necessary buffer to compensate for less-than-ideal targets and environmental degradation. Furthermore, considering the minimum range is vital for applications where objects can get very close to the sensor face.

Calibration and signal processing are essential for maintaining accuracy across the entire range. Many modern sensors incorporate internal algorithms to compensate for non-linear responses. Regular calibration against known distances, especially under the specific environmental conditions of the application, ensures ongoing reliability. Understanding the range specification in the context of accuracy is also key. Accuracy is often not constant across the range; a sensor might be very accurate in the middle of its range but less so at the extreme minimum or maximum distances. The datasheet should be consulted for accuracy graphs or statements like "±1% of reading or ±2 mm, whichever is greater."

In summary, the distance sensor range is a foundational specification that dictates the feasibility and performance of a sensing application. It is a variable figure, deeply influenced by the sensor's technology, the environment, and the target itself. Successful implementation requires moving beyond the datasheet's ideal numbers to a holistic understanding of these interacting factors. By carefully matching the sensor's range capabilities to the real-world demands of the application—while building in a healthy safety margin—engineers and designers can ensure robust, accurate, and reliable distance measurement.